I saw the snares that the enemy spreads out over the world and

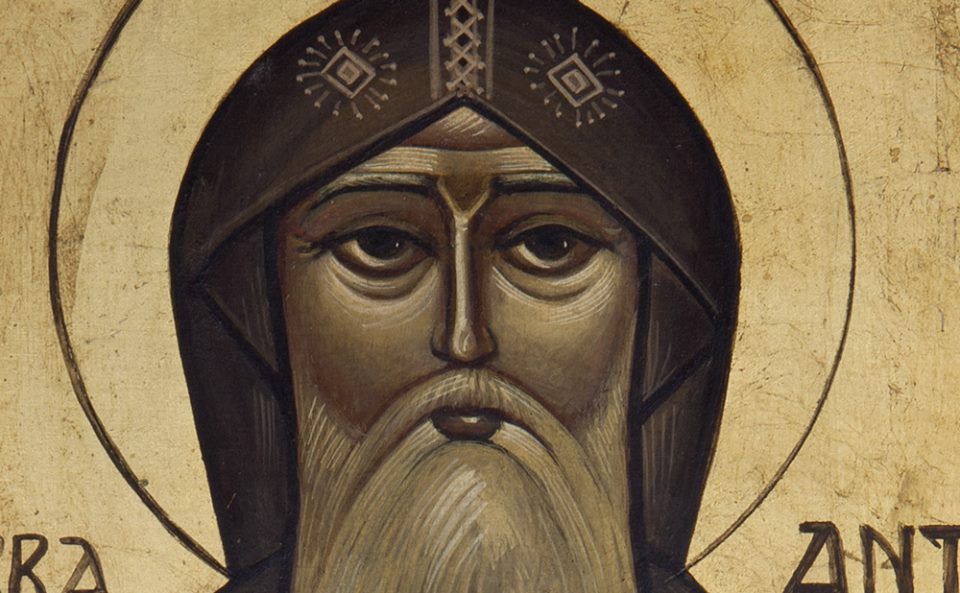

Abba Antony

I said groaning, “What can get through from such snares?”

Then I heard a voice saying to me, “Humility.”

Saint Antony of the Desert (251–356 CE), whose feast we celebrate on January 17, is widely considered to be the father of desert monasticism, a movement that flourished in Egypt at the same time as the persecution of early Christians was coming to an end. This was a time of seismic transition, as Christianity was becoming the official religion of the Roman Empire with the conversion of Emperor Constantine I. Although this was a heady time for many religious leaders, others foresaw the wedding of Christian faith with imperial power to be a corruptive seduction that would only undermine the Gospel and deceive many people into following a “cross-less” faith. Thus, Christian hermits and their followers fled into the desert by the thousands to pursue a “bloodless martyrdom” defined by extreme ascetic practice, solitude, contemplation and prayer.

Antony was by no means the first in this tradition, but his life and witness – interpreted and written down by his contemporary Saint Athanasius – quickly became paradigmatic for the way of salvation. His life serves as a testimony to the astonishing process of divinization (or theosis) of the human person by the pleasure of Christ who “became like us so that we might become as he is” (Irenaeus).

Antony was born to wealthy, devout parents and was known as an uncommonly content and obedient boy. Being a somewhat solitary child, not one to pursue childhood friendships, he was said to live in “reflective affluence.”

Both of Antony’s parents died when he was 18 years old, leaving him with a large inheritance and the charge of his younger sister. One day, only months after his parents’ deaths, Antony was pondering the biblical account of the early Christians who sold their possessions and laid the proceeds at the apostles’ feet for distribution among the poor. That same day, the gospel reading at church had recalled Jesus’ words to the rich young man: “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Matthew 19:21). Antony perceived these words as spoken directly to him, and he immediately went out to disburse his landholdings and monies among the poor, leaving just a modest amount for him and his sister to live on.

Weeks later, again at church, Antony heard Jesus’ words “Be anxious about nothing” (Philippians 4:6). Soon after this, he gave away what little he had retained of his inheritance, and placed his sister in the care of nuns before setting out to pursue a solitary life in the desert. Under the watch of an older hermit who trained him in the disciplines of ascetic spirituality, Antony began his pursuit of Christ and Christian virtue.

The rest of Antony’s long life was an ever-deepening journey into the desert. Stories recount how Satan and his minions pursued and tormented Antony with a fury – often keeping the saint awake all night with terrible screeching, visions of ferocious, ravenous animals, and seductive apparitions of alluring women. Antony remained undaunted, calmly reminding Satan that he himself was but an apparition with no substance – just as darkness has no substance but is, rather, the absence of light. On one occasion, Antony cried out in frustration to his tormentors, “It is a mark of your weakness that you mimic the shapes of irrational beasts!” Thus, his biographer writes, “after trying many strategies, they gnashed their teeth because of him, for they made fools not of him, but of themselves.”

After many years of solitude in the desert, purifying his soul through the practice of prayer, recitation of scriptures, and ascetic disciplines for the reordering of disordered affections, Antony emerged from his cell with a bright countenance, “as if from some shrine, having been led into divine mysteries, and inspired by God… The state of his soul was one of purity, for it was not constricted with grief, nor relaxed by pleasure, nor affected by laughter or dejection.”

Eventually, the solitary hermit found himself surrounded by thousands (Athanasius suggests a “city”) of souls who, like the demons, followed him into the desert. But unlike those clawing beasts, these were souls drawn to a light that the darkness could not extinguish.

Antony became a mentor to peasants and princes. Though uneducated, his speech was said to be eloquent and grace-filled. He healed those with ailments, consoled the grieving, reconciled the hostile and, above all, urged everyone to “prefer nothing in the world above the love of Christ,” thus registering themselves for “citizenship in the heavens.”

I read the The Life of Antony when I was a younger man during a terribly restless time in my life. After reading his story, I increasingly began to actively pursue regenerative solitary experiences, which have profoundly nourished my naturally distracted, extroverted and passion-weary soul. The song “Fashion for Me,” found at the end of this chapter, emerged from those early experiences of solitude.

I read of Antony’s life again in preparation for this brief account. Then today, before beginning to write, I read the book’s introduction once more. The author of the preface, William A. Clebsch, illuminates something that struck me just now for the first time. He writes that Antony was “eminently convertible,” suggesting it was this particular quality – a persistent openness to transformation – that made for such a remarkable life.

It wasn’t so much Antony adopting his parent’s Christianity in childhood that was so unique – as if salvation is inherited – nor was it a one-time event clearly demarcating a before and after. Rather, it was his conversion in early adulthood to a relentless convertibility – “the convertibility of one en route to Christian salvation” – that has humbled and inspired countless people after him to resist the colonizing of our faith by principalities, powers and seductions whose substance, in the end, is mere phantasm.

May our grateful remembrance of Antony, and countless others after him, inspire in us relentless convertibility – for Christ’s sake, for our own soul’s sake, and for the life of the world.

FASHION FOR ME

Music and lyrics by Steve Bell

Fashion for me a desert of peace

Appears on the 2012 CD release: Steve Bell / Keening for the Dawn

A land that is empty of endless dis-ease

With no one to suffer, hate or appease

With nothing to covet, desire or compete

But You alone

Grant to me Lord by Your sovereign hand

To wander forever in this boundless land

Where all of my yearnings, fears and demands

Are abandoned and lost to the great desert sands

Surrounding me

Fashion for me a desert of peace

Where Father, Son and Spirit meet

Together as one, together release me

Free from sin to enter in

To life forevermore

Fashion for us a city of love

Where the lamb and the lion together lie down

Where all of the wandering pilgrims are found

Rejoicing in song for the Saviour is crowned

As Lord and King

Grant to us Lord by Your sovereign hand

A city of joy in the heart of the land

A home for the weary alien man

The fatherless children, the widow whose hands

Are tired and worn

Fashion for us a city of love

Where Father, Son and Spirit live

Together as one, together allow us

Free to take and celebrate

The life forever more