The following article was published in The Anglican Planet, May 2015 edition.

I understood my baptism would be a mere formality. In other words, I really didn’t expect much from it. Honestly, my low-church Baptist heritage taught baptism to be a mere obedience, as opposed to the high-church understanding of baptism as a sacrament. Even so, if a sacrament is an outward sign of an inward reality, then my baptism—performed by my proud father when I was the tender age of nine—simply formalized something that was, for me, an extension of my “conversion” experience two years earlier at Daily Vacation Bible School, when I publicly declared what I had always known and believed to be true—for I’ve been a Christian as long as I have memory, and probably sometime before.

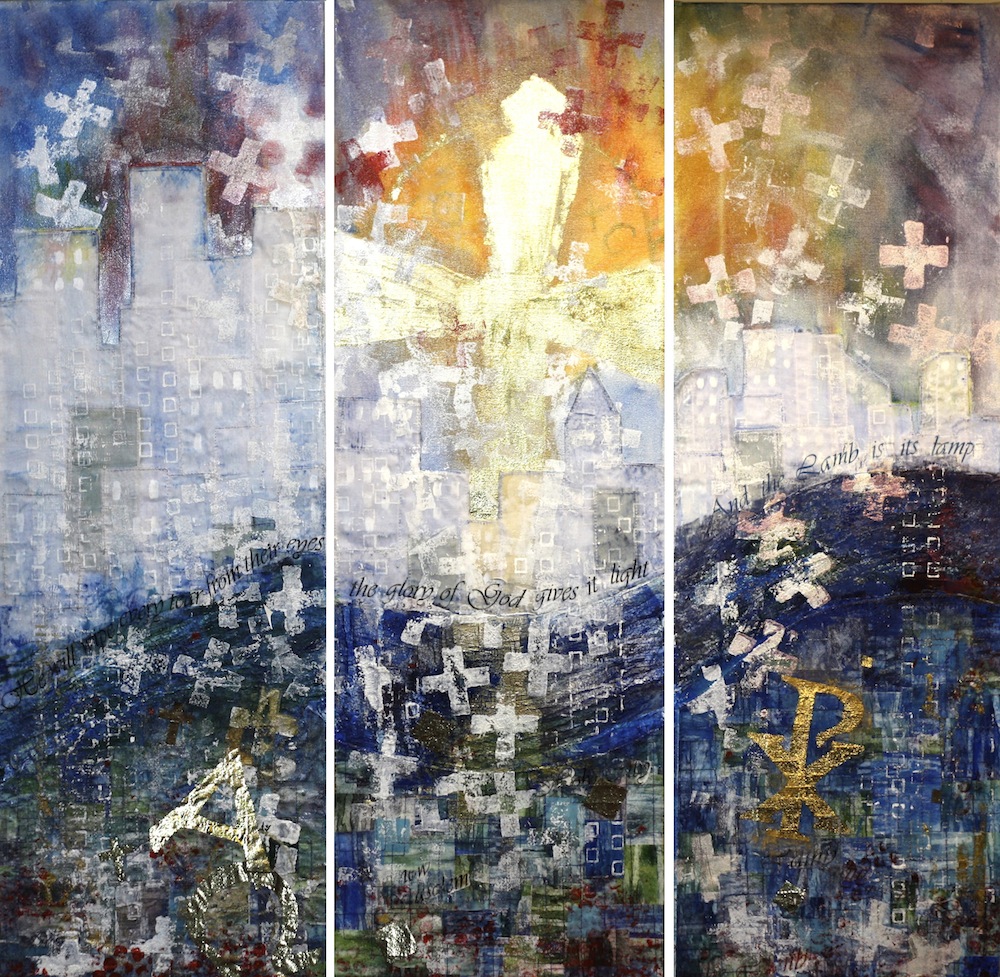

And yet, my baptism changed everything. I came out of those waters feeling like a cross had been etched on every fibre of my being. I was no longer my own. I now belonged to Christ, and my understanding took on cruciform spectacles that have progressively clarified my vision since, affording me to walk through this world of woe with a confidence and hope despite the evidence of its fragmentation and corruption, and my own sometimes-willful complicity in it. For “yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,” I am indeed in Christ, as he is in me, and we are in God, in the loving fellowship of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, now and forever, and unto the ages of ages!

***

For the early church, the significance of the liturgical Lent-Easter sequence lay in her contemplation of Jesus’ baptism by John, and his forty-day trial in the desert, prefiguring his own passion, death and resurrection. Imitating Jesus’ experience, new converts were expected to undertake austere preparations for forty days (this is the beginning of the Lenten tradition) prior to their baptism, which would take place during the Easter vigil in joyful anticipation of their symbolic resurrection with Christ on Easter morn.

It is interesting to note here that the Eastern church respectfully, and understandably, objects to the Western church’s adoption of the word Easter (instead of the more traditional Pasha) to name the sacred feast of Christ’s resurrection. According to St. Bede, Easter derives from the pagan dawn-goddess Oester, who was associated with renewal and fertility, traditionally celebrated on the March equinox, which signalled a lengthening (lent) of days and return of spring.

Perhaps the Western church can be granted modest kudos for this particular insight and innovation. It is part of the genius of the Western church to have been able to take existing pagan words and practices, and to in a sense “baptize them” in the name of Christ. Oh that the missionaries to North America had done the same with indigenous practices!

Traditionally the Easter vigil was a service held in the hours of darkness between sunset on Holy Saturday and sunrise on Easter morning. Since liturgical days were considered to begin at sunset, this was the first official celebration of Easter. The key, then, to a Christian recasting of the pagan celebration of the dawn-goddess Oester, is in our understanding of our own baptism into the life, death and resurrection of Christ, which re-orients us toward the true east from which the Sun of Righteousness dawns. This is why the early church baptized new converts during the Easter vigil, just as the darkness was abating and dawn came over the horizon.

Moreover, this re-orientation and clarified vision suggests a cleansing and opening to newness (epiphany) that traces back to Jesus’ baptism in the river Jordan.

***

I’ve been there—to the banks of the mighty River Jordan that is. It’s not all that impressive actually, although some claim it may well have been before modern irrigation siphoned away its visual significance. Yet, somewhere between the Jordan’s birth at Galilee and its death at the Dead Sea, Jesus was baptized by his cousin John, forever sanctifying water to cleanse and restore humanity to the dignity of daughters and sons of God.

More than that, Jesus’ baptism revealed something entirely new, from which every baptism derives astonishing significance. As he rose from the waters of his baptism, scriptures report that the heavens split, the dove of God’s spirit descended, and the voice of God’s fatherhood spoke, “This is my son!” And there, for the first time, creation apprehended its Creator whose image it dimly reflects—for God is revealed here, not a lonesome cosmic deity as once assumed, but rather as a familial community (com-unity), eternally satiated in mutual, self-donating love.

What we often don’t fully appreciate is that Jesus’ baptism not only reveals his divinity, but from this symbolic gesture of an individual death arises the revelation of God’s tri-unity. From here, then, we begin to apprehend the significance of the death of our own egocentric individuality, and resurrection into the altrocentric com-unity that is God’s nature from which all creation springs.

A few years back, I began to attend much more deliberately to the ebb and flow of the Church calendar year with her various feasts, fasts and saint’s days as a way to give shape and direction to my journey to God. Up until then, my own Christian pilgrimage seemed somewhat directionless, and any moments of consolation, rest or illumination were mere happenstance. Attending to the seasons gave my walking a sense of deliberateness and ascent. I began to imagine every remembrance, fast or feast as an individual peak in a mountain range, each with varying height and significance. Some resembled foothills and some rose to majestic heights, the loftiest of which were shrouded in cloud (mystery), making their relative heights hard to assess; yet each contributed to a gradual ascent of illumination and apprehension of God—and by extension, the meaning of our own humanity. I had always assumed the feast of Christ’s resurrection to be the utmost peak in this magnificent range. As I stepped back for a more careful look, however, I noticed that Lent and Easter were flanked by the feast of Christ’s baptism, a penultimate summit for rest and nourishment before making the final and arduous climb through Lent and Easter to the loftiest summit of all: Trinity Sunday.

Could it be that the church—both East and West—unwittingly completes its yearly pilgrimage one mountain-peak too soon? We assume the resurrection of Christ to be the summit of God’s revelation and love. Perhaps tradition places Trinity Sunday at the end of the season of Eastertide and at the beginning of Ordinary Time as if to say: “Trinity is the new normal.” Or, better yet:

Divine love (self-giving mutuality) is the renewed normal!

Indeed, this is a worthy summit on which to plant our flag.

My baptism may well have been a formality, an exterior marker to signify an interior reality. But I’ll never forget that sense of having been “etched.” I couldn’t, at nine years old, have understood I had been marked and set off on a pilgrimage—an arduous ascent through sometimes perilous, and sometimes exhilarating terrain— toward a summit whose peak I would only occasionally glimpse along the way. And yet, I feel as though I’ve been journeying to that which I already know… indeed, have always known. For insomuch as “Christ in me” also means “I in Christ,” it’s a journey already taken in its fullness. Therefore my own journey, though sometimes a trail of tears, also has a certain lightness of step, and a melody to hum and whistle along the way; for indeed, divine love is the renewed normal—both now, and forever, and unto the ages of ages.