John’s gospel is all about the marriage of heaven and earth in Jesus Christ … not the separation of heaven and earth but their wonderfully fruitful combining.

N.T. Wright

“The Hour Has Come,” reprinted sermon, http://ntwrightpage.com/2016/04/25/the-hour-has-come.

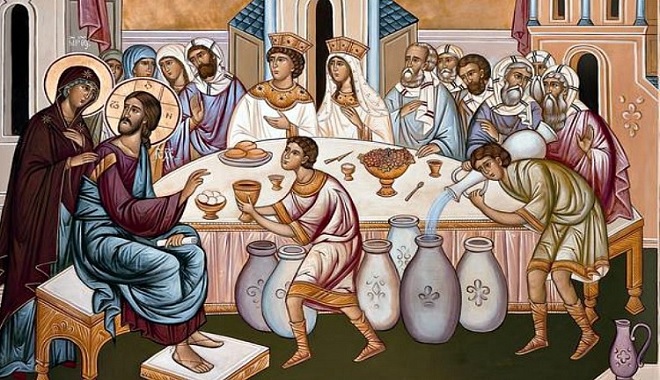

Now we come to the story of the wedding feast of Cana where Jesus miraculously turns 150 gallons (more than 600 litres) of water into roughly 800 bottles of wine – rather fine wine, apparently – after supplies ran out at a local wedding banquet.

Either the wedding was poorly planned or significantly more guests had shown up than had RSVP’d, or it was one of those nights when joy had simply come off the hook, suppressing good sense and moderation. Either way, according to John’s Gospel, Jesus’ miraculous response to the incident revealed his glory and thus inspired his disciples to put their faith in him (John 2:11). And if the Gospel makes such a claim, then we should sit up and take notice.

If I were to title this passage, I would be tempted to call it “The Story of the Prodigal God.” For the word ‘prodigal’ doesn’t have to mean imprudently wasteful in the morally contemptuous sense, but can also be taken to refer to a display of generous, lavish abundance for no practical reason other than the sheer joy of it. I believe it was Henri Nouwen, reflecting on the parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke’s Gospel (15:11-32), who pointed out that the Father’s prodigious love for his boy far exceeded his son’s wanton excesses, revealing a divine prodigality that joyfully surprises. It seems to me that this story bears a similar, if not brighter yet revelation.

What a revelation it is! Remember that this is the third major feast of the season of Epiphany, which sheds a particular light on the Incarnation (the Word made Flesh), revealing the glorious divinity of the very human Jesus. First, we recall the gratuitous revelation to the magi (Gentile outsiders) who were literally ‘enlightened’ by a star. Next we recall the baptism of Jesus, which reveals his divine sonship in the dynamic relationality of God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Now, we consider the revelation at the wedding feast of Cana, which is a bit earthier and even a little bit fun because, on first blush at least, it reveals that God seems to appreciate, and is pleased to bless, a roaring good party. And that is delightful in itself.

But this isn’t just any party. It’s a wedding feast. According to theologian N.T. Wright, this detail is not insignificant in that the whole of John’s Gospel is at pains to reveal the marriage of heaven and earth as the ultimate goal and joy of salvation, of which every wedding feast is a marvellous sign:

John’s gospel is all about the marriage of heaven and earth in Jesus Christ. That is the final purpose of God in creation – not the separation of heaven and earth but their wonderfully fruitful combining.

N.T. Wright

“The Hour Has Come,” reprinted sermon, http://ntwrightpage.com/2016/04/25/the-hour-has-come.

So, even if Jesus at first responds a bit grumpily to his mother’s suggestion that perhaps he (whose hour had not yet come) could do something about the disastrous wine shortage, one can sense that the resulting excess of wine reflects in him a giddy superabundance of joyful anticipation of what is sure to come.

But, like any good story, there is a shadow cast as well, which causes one to suspect this new wine is not a thin bubbly, but a rather rich, blood-red vintage. The story opens with the cryptic words “On the third day there was a wedding…” (2:1). Anyone remotely familiar with the story of Jesus will immediately feel the foreboding weight of these words. For even if, according to our creed, Jesus rose triumphant on the third day, the implication is that he did so having passed through Good Friday and Holy Saturday – that is, through giving his life over to death so that we, in him, might have life. If, as N.T. Wright suggests, John’s Gospel is at pains to reveal salvation as the marriage of heaven and earth (experienced in resurrection), it is also at pains to reveal the self-sacrifice of Christ in order for it to be so. Here again, the metaphor of a marriage is revealing. For, in the Orthodox tradition at least, marriage itself is considered a martyrdom. It is accomplished through the willing death of the ‘me,’ in order for a fruitful ‘we’ to emerge. Given the anticipation of the resurrection life embedded in the mystery of marriage, it should surprise no one that the crowns placed on the heads of the bride and groom in a traditional Orthodox wedding are meant to symbolize a martyr’s crown.

In an unpublished foreword to his poem Epiphany at Cana, Malcolm Guite writes:

But the most important sign, the most important ‘epiphany’ in this miracle, is how it points to and reveals God’s very self, his innermost generous heart. For this wine – symbolizing God’s salvation – is not free; it is going to cost Jesus everything. That is why at first he tells his mother “My hour is not yet come.” This wine of transformed living comes to us at the cost of Jesus’ own heart’s blood, given once for all on the cross, and received by us in communion.

Malcolm Guite

When I was a child, I loved this story because Jesus seemed to be simply doing something nice. And he certainly was. That, too, is part of it. For who can’t imagine the relief of those spared the embarrassment of a major social faux pas, or the delight of those with an empty glass who thought a good party cut short only to discover it had just begun, or the raised dignity of the astonished serving staff who were blinkered accomplices to the miracle? Whose heart can’t thrill to the realization that this world we love so much, and the very matter which makes it what it is, is not after all destined for obliteration, but rather, under the sign of resurrection, for transformation from within?

The Miracle at Cana

By Malcolm Guite

Here’s an epiphany to have and hold,

Sounding the Seasons: Seventy Sonnets for the Christian Year (Canterbury Press, 2012), 23.

A truth that you can taste upon the tongue,

No distant shrines and canopies of gold

Or ladders to be clambered rung by rung,

But here and now, amidst your daily living,

Where you can taste and touch and feel and see,

The spring of love, the fount of all forgiving,

Flows when you need it, rich, abundant, free.

Better than waters of some outer weeping,

That leave you still with all your hidden sin,

Here is a vintage richer for the keeping

That works its transformation from within.

‘What price?’ you ask me, as we raise the glass,

‘It cost our Saviour everything he has.’