Now is the time to loosen, cast away

Malcolm Guite, Sounding the Seasons, 41.

The useless weight of everything but love.

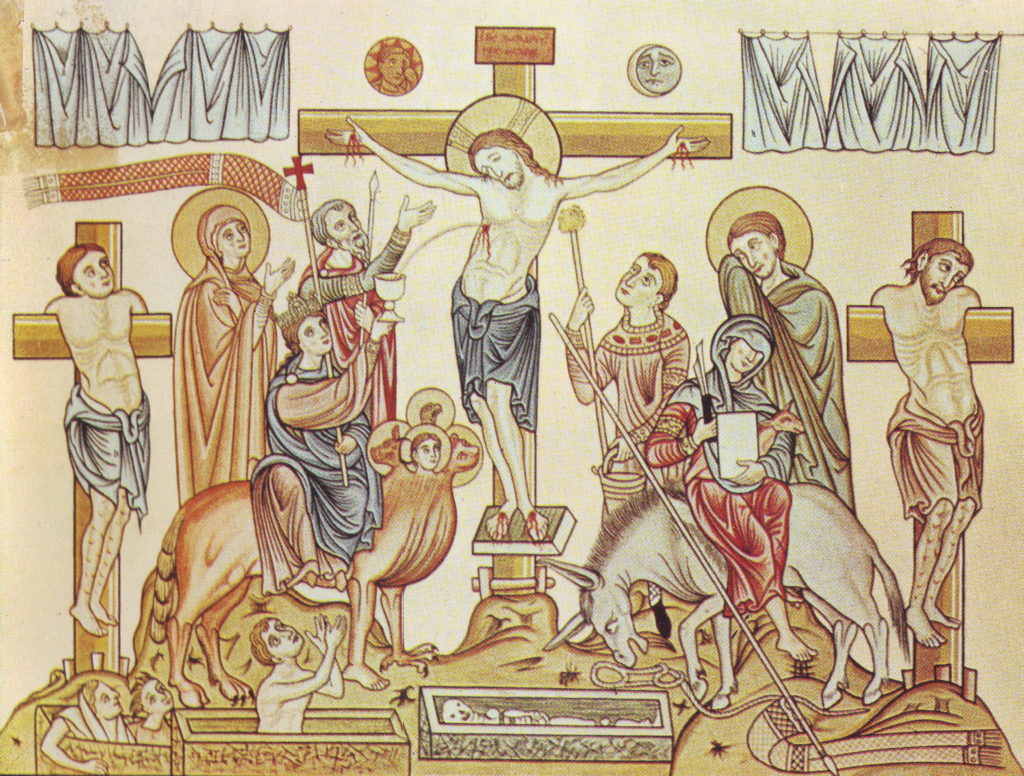

Good Friday is the day the Church commemorates the betrayal and rejection of Jesus by his own people and his subsequent torture and crucifixion by Imperial Rome: “Rejected,” according to German theologian Jürgen Moltmann, “by inhuman persons because of his love for those whom they dehumanized.” (Jürgen Moltmann, The Crucified God (Fortress Press, 1987), 89). For indeed, besides challenging the religious powerbrokers of the day, Jesus impiously crossed social norms by elevating the lowly, embracing the forsaken and forgiving the sinner.

Paradoxically named, Good Friday is the terrible and disorienting day when the “treachery of men” and the “blackest ingratitude” (Gabriel, Divine Intimacy (Ignatius Press, 1987), 405) seem to all but swallow whole our hopes for a brighter morning. It is also a day when we consider our own broken and sinful complicity in all that divides and destroys the whole-some creation that God lovingly made and called very good.

Further, Good Friday is the day when, as our faith teaches, Christ collected the world’s sorrows and sins, self-inflicted as they often may be, and bore them to the grave revealing the “delicate devices of his immense charity.”(Gabriel, Divine Intimacy, 40). It is good because this day, according to the Baltimore Catechism, “showed his great love for [us] and purchased for [us] every blessing.” (http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-27067136) Good Friday, then, is consistent with the birth of Emmanuel (the humble condescension of God to the level of our apprehension), counter-intuitively blessing our injured and injuring creatureliness, revealing a depth of God’s redeeming commiseration with our humiliations and sufferings that can only be responded to with blinkered and grateful thanksgiving.

As a result, there can be responses to this day that are both different and equally legitimate. I’ve participated in Good Friday services that are more celebratory than sorrowful. These are more common in Protestant traditions that tend to emphasize the victory of the cross rather than the sorrow of it. Because, after all, don’t we know that Sunday is coming and that death is not the last word? Don’t we already know the joy of resurrection?

But we also know that our own sinful opposition to love continues the conditions for which Christ suffered and died and which keep us, and others, imprisoned and alienated from Easter joy. Even though this day is good indeed, it is important that we speak the truth of our lives – our wounded condition and wounding dispositions that the cross of Christ absorbs and redeems. This is the time, pens the poet Malcolm Guite, “to loosen, cast away / the useless weight of everything but love.” (Malcolm Guite, Sounding the Seasons, 41)

In The Crucified God, Moltmann argues that the first word of the cross is not victory, but rather identification and solidarity with all whom lovelessness has cast to the outer margins: the rejected, the dispossessed, the dehumanized and the abandoned. This surprises, given that the power and glory of gods and demigods, as the ancient world (and indeed our own) would understand it, does not commiserate with outcasts and losers. Power and glory are the reward of winners, not losers. However, the cross reveals that the epicentre of the power of love is wherever Christ is to be found, even if that be hung and humiliated between scoundrels and thieves. An ancient text speaks of the glory of God whose “centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” (For a brief historical background to this quotation, seewww.artandpopularculture.com/Sphere_having_its_center_everywhere_and_its_circumference_nowhere -accessed June 18, 2018).

It reveals that God is first with us in our bleakest, most desolate state before he is for us as our rescuer or saviour. In hindsight, it also reveals that Resurrection – the “big bang” (so to speak) of the new creation – begins in darkness before it explodes into light.

First-century folks, who experienced this story in real time, didn’t have the luxury of knowing where it was going. Neither do so many today. This, of all days, is a day to come alongside the desperate ones who can’t quite imagine resurrection in either the temporal or the eternal realm. It is a day to pray for those who can’t pray for themselves and to suffer with (com-passion) those for whom “progress” has been unkind. And it is a day for fearless moral inventory, acknowledging truthfully our complicity in the things that make for our own and others’ sorrows.

Each year, my wife and I have two traditions on Good Friday. First, without fail, we watch the movie Jesus Christ Superstar. We’ve watched it so many times that we can sing along to almost every word. I love how the Jesus story translates into the revolutionary aspirations of the hippy movement of the late 1960s and early ’70s, confounding utopian hopes and exposing the logical absurdity of the cross as a revolutionary tactic. Judas’ bewilderment and incredulity gives voice to our own as he sings, “Jesus, I just don’t understand….”

Second, we always attend a Tenebrae service. The word “Tenebrae” comes from the Latin word for darkness; liturgically, it refers to the ancient Christian tradition that makes use of gradually diminishing light through the extinguishing of candles to symbolize the events of Holy Week from the superficial triumphalism of Palm Sunday through to Jesus’ execution. Traditionally, the service has been held in the darkness of the last three nights preceding Easter. If Judas’ words in the imaginative musical are spare and stark – “Jesus, I just don’t understand” – more so are the words of scripture, which simply say, “and they crucified him.”

With those four words we come to ground zero. The unthinkable and irreversible has happened. Love itself, it seems, has been vanquished, and all hope is lost. Yet, this garden of tears is the place where we must wait patiently, prayerfully, expectantly. Because, to quote a friend, the most likely place to witness a resurrection is in a graveyard.

I hope the reader will go to this book’s companion website to listen to the song below. It echoes the heart’s most desolate agony, as it does from among the last words of Jesus before he draws his final breath. But nearing the end of the song, when there are no more words to sing, the distant drums continue to thunder and broil, and the human voice keens wordlessly while the strings ebb and flow in a mournful surf. Then at the very end, when it seems there can be no hope for newness, the drums stop at the moment the strings turn and lift like the sound of a sudden gasp of breath from a dead body.

GONE IS THE LIGHT

music and lyrics by Gord Johnson

Into the darkness we must go

Appears on the 2008 CD release: Steve Bell / Devotion

Gone, gone is the light

Into the darkness we must go

Gone, gone is the light

Jesus remember me

When you enter your kingdom

Jesus remember me

When your kingdom comes

Father forgive them

They know not what they do

Father forgive them

They know not what they do