HOLY WEEK DESCENT INTO DARKNESS

Below, you can watch a new video we just released for the title track of my latest album, The Glad Surprise. It feels fitting to release this at the beginning of Holy Week.

In a reflection about Holy Week, I once wrote:

Whereas Advent can generally be described as an ascent to light, Holy Week, by contrast, moves us in the opposite direction – in a descent into darkness. Even though we, by faith and hindsight, might be tempted to look past the darkness of Good Friday to the bright dawn of Easter morn, we are invited to enter imaginatively into this time, suspending our foreknowledge of the Resurrection so that we, like Mary at the foot of the cross, may stand in solidarity with all those who know of no such hope…

This song (and video) is a bit of a departure for me. It’s not as comforting or serene as folks have come to expect based on past work. But it came unbidden, as most do. Honestly, with this song (as with others like Burning Ember and This is Love), I feel more like a scribe than a creator.

Below is the video, followed by my reflections about the song, which I wrote for the album’s liner notes.

Watch:

THE BIRTH OF A SONG

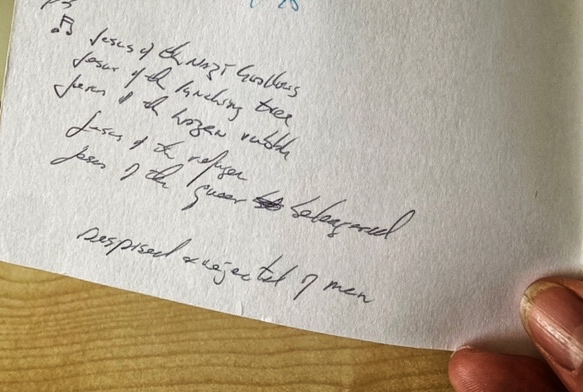

I was only five pages into Reggie L. Williams’ book, Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance (Baylor University Press, 2014), when I suddenly turned to a blank page on the inside of the book’s cover and wrote:

Jesus of the Nazi gallows

Jesus of the lynching tree

Jesus of the Gazan rubble

Jesus of the refugee

Jesus of the queer beleaguered

I left a space and then wrote,

Despised and rejected of men

The lines came almost involuntarily. They felt more like a cough that escaped suppression than a careful articulation of a thought or thoughts. I also placed a pair of music notes beside the lines, which, if you sift through my bookshelf, you’ll soon realize I place beside anything I think could be a potential song. However, I do remember thinking, “Well… I can’t write that into a song… that would get me into all sorts of trouble.”

But there it was. For days, it felt like an annoying sliver in my finger… something I could mostly ignore, but that kept drawing my attention whenever there was a quiet moment.

Eventually, I opened the book again and stared at the front page. A melody started to form. And another line came:

Jesus of the hunted child

I thought of the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt—escaping Herod’s wicked pogrom intended to eliminate potential threats to his power, and I couldn’t help but feel the desperately anxious centuries of fleeing families whose only crime is that their very existence places moral limits on another’s unholy ambitions.

A few days later, in conversation with my co-worker, Jay Johnson, another line came:

Jesus of the missing women

Native to the sacred wild

Canadians will recognize the reference here to the dangerous and degrading attention/inattention that First Nations people suffer under our justice system.

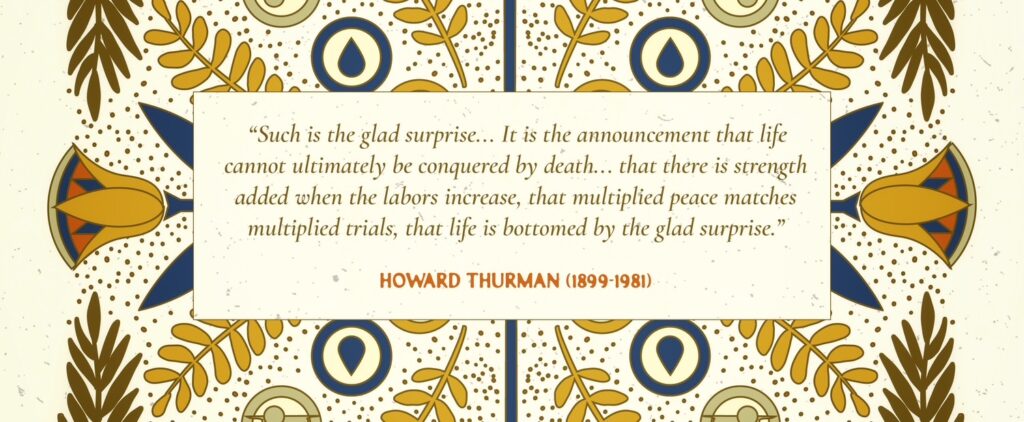

Before reading Williams’ book, I read Howard Thurman’s classic Jesus and the Disinherited (Beacon Press, 1976). Thurman’s work is widely regarded as the theological backbone of the civil rights movement. Indeed, he was a spiritual advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., and it is reported that King carried a copy of Thurman’s book wherever he went.

The central thesis of Jesus and the Disinherited is that the Cross of Christ reveals that God will ever be found beside and among those “with their backs against the wall.” For Thurman, this is the hermeneutical key that unlocks the mystery of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Thurman’s Jesus reveals a divine humility that ultimately “can’t be humiliated” even though “too often the weight of the Christian movement has been on the side of the strong and powerful, and against the weak and oppressed.”

To all this, one can only respond with an awe-filled doxology:

Oh! What love!

ENTER MALCOLM GUITE

I sat on those first stanzas for several weeks with no idea how to complete the song until I finally did what I now often do under such circumstances: I sent the lyrics to my friend, the English poet Malcolm Guite. I hoped he might suggest where I could take the lyrics next. All I knew was that I wanted to end with the line, “Jesus of the glad surprise.”

A day later, I received an email back. Malcolm’s good instinct was to extend the repeated preposition “of” to include “in” and “with,” which opened the song to a deeper Christology:

Jesus in the rolling waters

Jesus in the wind that blows

Pleased to hold “all things” together

Cosmic centre, mystic rose

Jesus with us from the cradle

Jesus with us through the grave

Jesus with a world against him

Ready nonetheless to save

I couldn’t help but recall a 12th-century definition of God that challenges the false binary between the divine universal and the divine particular: God is an infinite sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. (The Book of the 24 Philosophers – uncertain authorship)

Malcolm’s Jesus is, astonishingly, “in,” “above,” “with,” and “ready.”

Again… Oh! What love!

The closing stanzas return us to the Jesus of…

Jesus of the midnight struggle

Sweating blood to do Love’s will

Supple to the kiss of Judas

For his own betray him still

Jesus of the crucifixion

Darkness and despairing cries

Jesus of the great reversal

Jesus of the glad surprise

Struggling, sweating, despairing, dying… reversing, gladdening, suppling, surprising!

Oh, what love, indeed!

ABOUT THE MUSIC

In Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus, Williams claims that a year spent in the pews of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church while studying at Union Theological Seminary was formative to Bonhoeffer’s theology and his consequent resistance to German/Christian nationalism. That year (1930-31), “Bonhoeffer encountered the Christianity that animated the civil rights movement years before it occurred…”

Reading Williams, I suddenly remembered another child of the Harlem Renaissance theological tradition: jazz saxophonist John Coltrane. In his insightful book, God’s Mind in That Music: Theological Explorations Through the Music of John Coltrane (Cascade Books, 2012). Jamie Howison explores Coltrane’s celebrated recording, A Love Supreme. Re-reading Jamie’s book sent me scrambling back to Coltrane’s classic. To my delight, I soon realized that the signature four-note motif undergirding Coltrane’s first movement fit perfectly with the music I had written for this song.

And so, my album begins with a nod to Coltrane’s A Love Supreme in the opening bass notes, followed by an aching tenor sax played by Winnipeg’s Niall Cade, followed by a set of lyrics that cascade out of a torrent of dark waters, but which eventuate in a glad surprise.

Listen to “The Glad Surprise” album on your favourite streaming service, or order the CD/booklet at www.stevebell.com