Our perennial instinct to share food, drink and story as a response to grief and loss points to a gospel mystery that we’re all caught up in even if we don’t believe what our scriptures have been telling us all along.

I just received word that a friend has died after many months battling cancer. At this point, because of her long suffering, it doesn’t feel like the shock of catastrophe that the announcement of her illness first produced. Time has passed, we’ve tearfully said our goodbyes, we’ve tenderly blessed each other, and I’m now mostly relieved her long ordeal is over.

There will be a funeral, and I already know how it will go. Friends and family will gather in advance. We’ll speak in hushed tones about what a terrible loss this is, and what a shame that someone so young and full of life and promise had to go. We’ll also speak about the dignity with which she managed her last days. Then, during the service, tears will flow abundantly. We’ll suffer together, in community, the loss of our good friend.

Afterward, most will grimly file down to the basement where there will be a feast of buttered buns, cubed cheese, cold cuts, plates of vegetables, dainty desserts, coffee, tea and juice. The feast itself will at first be an affront. So we’ll huddle in various familial and familiar groups to absorb each other’s tears. But as we start to eat and drink, the mood will lighten. Slowly, laughter will start to erupt from this corner or that as folks retell a favourite story about our friend. Levity will enter the room as we feel the living goodness (miracle) of the community of which she and we are a part. Gratitude (Eucharist) will begin to displace grief, even if at first we feel guilty for it.

Perhaps our perennial instinct to share food, drink and story as a response to grief and loss points to a gospel mystery in which we are all caught up.

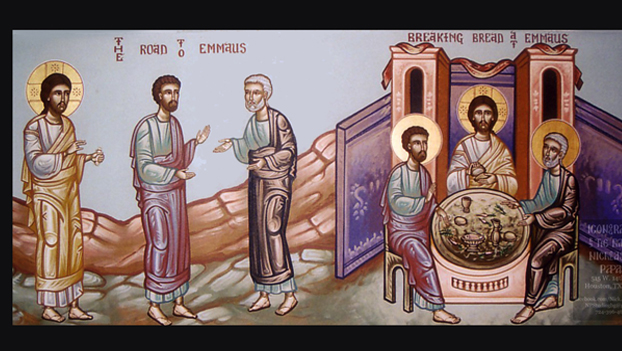

The Easter story of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, told only in Luke’s Gospel (24:13-35), might be the greatest revelation of this mystery that we have in scripture.

The Catholic scholar Jan Lambrecht has called this story one of Luke’s “most exquisite literary achievements.” This story, like so much of scripture, is first of all great art, not only chronicling events, but doing so in a manner that leaves us open to endless opportunities to discover and make meaning. So don’t be satisfied with my reflections here. There is much more. Second, let’s reflect on this story in light of the previous chapter about the so-called doubting Thomas. For here, too, the resurrected Christ allows himself to be seen in a manner that generates hope, joy and even, not blind faith, but Gospel belief.

Luke says that late in the day that Jesus rose from the tomb, two disciples were walking eleven kilometres to Emmaus. Who were the disciples? Scripture names only one, Cleopas, but many assume the other was his wife, Mary, whom John’s Gospel records being near Mary Magdalene,and Mary the mother of Jesus at the foot of the cross (John 19:25). Why Emmaus? We don’t know. Perhaps they were simply going home. Frederick Buechner suggests that Emmaus was no place in particular, except that it was “some seven miles distant from a place that had become unbearable.” (Frederick Buechner, The Magnificent Defeat (Harper, 1985), 85). Jerusalem for these disciples had been the scene of an unimaginable tragedy.

As they were walking, a stranger joined them and asked the downcast couple what they were discussing. They were incredulous! Had he really not heard what had happened? They told him that Jesus the prophet (notice that they didn’t say messiah or saviour, because it was inconceivable that the messiah could die on a cross), who was “mighty in deed and word before God and all the people,” had been sentenced to death and crucified.

Crucifixion was a Roman instrument of death designed not only to kill the person, but to kill, with maximum suffering and humiliation, any ideological hope for a reality that ran counter to Rome’s claim to imperial authority. Here we begin to understand that the grief on display was much deeper than for the terrible suffering and loss of a friend. It was also grief for the loss of hope for a future.

“We had hoped,” they said, “that he was the one who was to redeem Israel.”

Any one of us can begin a sentence with “We had hoped…” and then fill in the rest with any number of reasons for despairing the loss of hope.

To put some flesh on this, I was one who had great hopes for Barack Obama’s presidency, and, then struggled with some despair for how his work was systematically dismantled by the next administration.

We had hoped…

Hearing my lament, a dear friend of mine, of a different political persuasion, said that now I know how he felt when Obama dismantled the work of his predecessor.

We had hoped…

Many today are bewildered, dismayed and even traumatized by a faction of American Christianity’s apparent alliance with white supremacy.

We had hoped…

Others are devastated by the South American clerical cover-up of sexual abuse scandals.

We had hoped…

Yesterday I wrote a card to a young couple whose fifteen-month-old son recently died in a drowning accident. I admitted that I have no corresponding experience with which to imagine the depths of their heart-sickness. But I’m sure that if I get a chance to sit with them, part of their grief story will come out in the deepest lament for a future they will never now know.

“We had so hoped…”

The stranger lets the Emmaus pilgrims tell of their crushing disappointment and confusion. Then, Luke reports, the stranger opened the scriptures that tell the story they already knew but had been telling wrongly: that it would be through, and not around, suffering, that salvation’s glory would be revealed, and through which redemption of all (people and history) would come.

The travellers later recalled that at this point, their burdened hearts were turning into burning hearts. Shortly after, having asked the stranger to stay with them, the guest assumed the role of host; he took bread, blessed it, broke it and shared it. Here the penny drops. They recognize that the stranger was Jesus, and in a flash he was gone.

Luke then has the two running back to the epicentre of their catastrophe, joyfully announcing that the story was not over after all; that a hitherto unimaginable ending, or beginning, was now imaginable. In the words of N.T. Wright, “we need to listen for the hidden stranger on the road who will explain to us how it was that these things had to happen, and how it is that there is a whole new world out there waiting to be born, for which we are called to be midwives.” (http://ntwrightpage.com/2016/04/05/the-resurrection-and-the-postmodern-dilemma).

It shouldn’t be hard to detect a pattern of Eucharistic worship embedded in this story: When two or more are together, Christ will also be there. In that loving communion, we first break open the bread of scripture to be fed in our understanding. Then we bless and break the bread of Christ’s body to be fed in our spirits. Next, at a practical level, we share in the gift-bread of creation to be fed in our bodies, and to know, in our bones, that he is with us, and that we are united in our dependence on this present God for every gift pertaining to salvation and eternal life.

Let us pay attention to, and fan into burning flame, our human instinct to share food and drink hospitably, especially in the context of tragedy and loss. During these times we are participating in revelation, in Gospel hope and in loving witness to the redeeming love of God in Christ. It is Christ who will, in the fullness of time, redeem and draw every tear, every dashed hope, every broken heart, to the eternal banquet of God’s kingdom. Until then, we will continue to take bread, bless it, break it and share it – symbolically, metaphorically and really. In doing so, the risen Christ is present, even now.

JESUS, FEED US

music and lyrics by Gord Johnson

Again and again and again

Appears on the 2008 CD release: Steve Bell / Devotion

To this table we come

Once a people estranged

Now as one in your name

Forgiven of all we’ve confessed

By your body and blood

One last thing we request

Feed us Jesus

Jesus feed us

Feed us Jesus

With your healing love