God has helped the house of misery!

The tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates the resurrection of Lazarus on a Saturday (Sabbath), the final day of creation, thus making it also a foretaste or signpost of re-creation. It is poetically poignant that Lazarus Saturday falls on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day Jesus set out from Bethany on a donkey to goad the great and final confrontation by which he conquered death through death.

The story is found in John’s Gospel (11:1-45) and is worth reading slowly to catch the many nuances of meaning.

We read how Jesus, as he comes upon his grieving friends Mary and Martha, the sisters of the recently deceased Lazarus, is himself overcome by grief. Scripture gives us that wonderful verse, “Jesus began to weep” (11:35).

We see Jesus as very human, subject to sorrow and acquainted with loss. Later, we hear him cry in a loud voice, “Lazarus come out!” (11:43), and glimpse him then as the God whose word calls light out of darkness, life out from death.

This passage also records the wonderful discourse with Martha when Jesus staggers comprehension with the claim “I AM the resurrection!”

Jesus said to her, “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him, “Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.” (John 11:25-27)

The word ‘resurrection’ is cognate with the word ‘resurgence.’ Thus, Jesus is claiming to be (in his very being) the surprising resurgence of Life itself, which, in the case of Lazarus, appeared to have been extinguished.

Ironically, Jesus was mistakenly labelled and executed as an insurgent when he was actually a resurgent. Denying this difference was a tactical error made by God’s enemies, the Kingdom of Darkness, whose apparent victory at Golgotha was the means by which it was fatally infected with the Gospel virus.

The meaning of the names in this passage is intriguing. First, the name ‘Lazarus’ means God has helped, signifying God’s orientation toward the helpless. Second, the name ‘Bethany’ – the village where Lazarus lived and from which Jesus staged his triumphal entry into Jerusalem – means house of misery or poor-house.

Scholars assert that Bethany was populated with the unwell and the poor. This is where Simon the Leper lived (Mark 14:3-9). It is also where the disciples objected to Mary’s extravagant anointing of Jesus, which gave the context for his seemingly callous response: “the poor you’ll always have with you” (John 12:8). Given the attendant superstitions, alienating prejudices and wounding judgments surrounding issues of poverty and illness, it is doubtful that any self-respecting sovereign would have any association with this place, let alone call its inhabitants his friends.

But when you consider Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on a lowly donkey, a staggering picture emerges. The unique glory of this sovereign is not in the display of splendour and power common to disassociated sovereigns of the day, but instead is evidenced by his com-passion with the marginalized, the miserable and the defeated. The banner of his reign could be summarized with the tag line “Lazarus Bethany! God has helped the house of misery.”

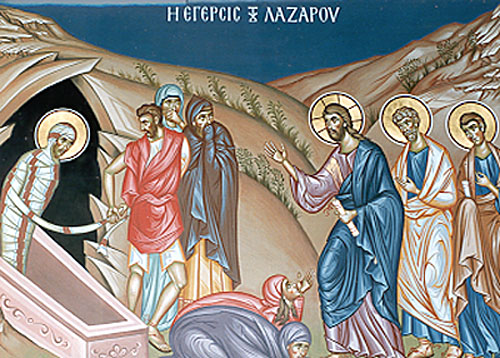

In preparing to write this chapter, I poked around the Internet in search of icons of Lazarus. One icon caught my eye: I was drawn to the contrast and tension of the image. Jesus is portrayed at the centre of the icon, stepping over a collapsed bridge, perhaps symbolizing the vain religious pretentions of Pax Romana. Behind him, huddled away from the cliff’s edge, are a group of well-dressed noblemen (Pharisees?) whose callous incredulity sullies their finery. Jesus himself inclines toward Lazarus in front of him. Lazarus is flanked by his sisters and friend Simon the Leper, whose humble attire contrasts with that of the noblemen.

In his left hand Jesus raises the heraldic cross, the emblem of his kingdom. In his right hand he holds the hand of lowly Lazarus who kneels on ground that is beginning to fall away.

The twin mountain peaks in the background perhaps symbolize the two natures of Christ: human and divine. The whole image is wreathed in greenery: the fresh life of vine and leaf.

Lazarus Saturday marks a significant shift in Lent – for from here, we enter into Holy Week, and we slow down almost to real time as the drama of God’s rescue unfolds. We have considered and repented tearfully of our collaboration with darkness. But our efforts now pale as the camera zooms in, as it were, on the Passion of Christ in his final days. A real but brief celebration occurs before all hell breaks loose. Then the fury will increase in intensity until it climaxes in the unspeakable.

Then, silence.

And then, well… wait for it!

BETHANY IN THE MORNING

music and lyrics by Steve Bell and Diana Pops

Praise the Lord, blessed be

Appears on the 2016 CD release: Steve Bell / Where The Good Way Lies

who has come to help the house called Bethany

and defends those broken friends

who’ve been crying.

Comes a light, breaks the dawn

Can you feel the ray of hope for those whose hope is gone?

Lift your head, dry your eyes

Time for rising

Praise the Lord, blessed be

Who brings comfort to the very least of these

In whose hands the journey ends

Joy surprises

From the east with every morn

Can you hear the voice that summons up horizon’s song?

Lift your head, dry your eyes

Time for rising

Praise the Lord, blessed be he

Anointed in the house of misery

Who defends the humble hands

That bode His dying

Who braved the night, retrieved the dawn

A ray of hope for those whose hope is gone

Lift your head, dry your eyes

Time for rising