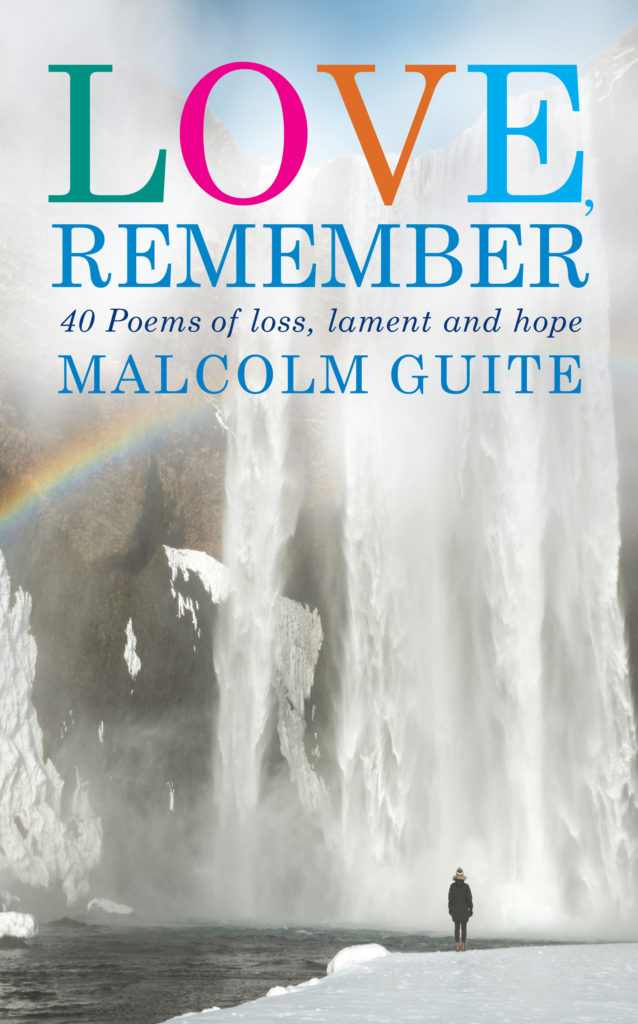

Last fall, Malcolm Guite sent me the manuscript for his then forthcoming, and now best-selling book, Love Remember: 40 Poems of Loss, Love and Hope in which Malcolm curates a sequence of poems, from Shakespeare to Luci Shaw, each accompanied by the kinds of reflections one might expect from a man who has committed his life to the power and beauty of words, theological scholarship, and pastoral care.

Last fall, Malcolm Guite sent me the manuscript for his then forthcoming, and now best-selling book, Love Remember: 40 Poems of Loss, Love and Hope in which Malcolm curates a sequence of poems, from Shakespeare to Luci Shaw, each accompanied by the kinds of reflections one might expect from a man who has committed his life to the power and beauty of words, theological scholarship, and pastoral care.

You might imagine how surprised and delighted I was to discover that he included lyrics to one of my songs in this anthology. They are lyrics I wrote which include two stanzas of a poem by Robert Louis Stevenson, an additional stanza from theologian N.T. Wright, and a couple stanzas of my own.

I wrote the song, in part, as my way of dealing with a cancer that was threatening to take my father’s life a couple of years ago. My father has miraculously survived the cancer, but the ordeal began a journey into loss and grief that I am still mining for meaning as I also consider my own aging and mortality.

In the introduction Malcolm writes:

This book is written to give voice both to love and to lamentation, to find expression for grief without losing hope, to help us honour the dead with tears, yet still to glimpse through those tears the light of the resurrection. It is written in the conviction that the grief that we so often hide in embarrassment, the tears of which some people would want to make us ashamed, are the very things that make us most truly human. Grief and lament spring from the deepest parts of our soul because, however bitter the herbs and fruits they seem to bear, their real root is Love, and I believe that it is Love who made the world and made us who we are.

An interesting insight I found on Amazon’s description of the book:

The choice of forty poems is significant and reflects an ancient practice still observed in some European and Middle Eastern societies of taking extra-special care of a bereaved person in the forty days following a death — our word quarantine comes from this. They explore the nature and the risk of love, the pain of letting go and look toward glimpses of resurrection.

Malcolm has graciously consented to me reproducing the chapter in this blog. For those dealing with grief, this collection really is a God-send. Purchase LOVE REMEMBER HERE…

Reprinted from LOVE REMEMBER: 40 Poems of Loss, Love and Hope | Malcolm Guite

Canterbury Press, 2017

CHAPTER 39: LET BEAUTY AWAKE

Stanzas: Robert Louis Stevenson (1-2), Steve Bell (3-4), NT Wright (5)

Let Beauty awake in the morn

from beautiful dreams

Let Beauty awake from rest

Let Beauty awake

For Beauty’s sake

In the hour when the birds awake in the brake

And the stars are yet bright in the west

Let Beauty awake from rest

Let Beauty awake in the eve

from the slumber of day

Awake in the crimson eve

In the day’s dusk end

When the shades ascend

Let her wake to the kiss of a tender friend

To render again and receive

Let Beauty awake in the eve

While we, the gardeners of creation blessed

Furrow the soil at our Saviour’s behest

And bury the seeds of our own life’s death

And suffer God’s glory to grow

Yes we the priests of all that is made

Gather the greatness of creation’s praise

That burgeoning freshness of glory displayed

From depths of the earth below

Let Beauty awake in the morn

From the cool of the grave

Beauty awake from death

Let Beauty awake

For Jesus’ sake

In the hour when the angels their silence break

And the garden is bright with his breath

Let Beauty awake from death

Today’s poem is the lyric of a song sung by the Canadian musician Steve Bell and taken from his wonderful album Where the Good Way Lies. But it is more than that, it is a collaboration across the continents and the centuries between the arts and the scriptures. For that reason, it is also an epitome of what I hope to do in this anthology, bringing many disparate sources together in a single work, whose purpose is both to express grief and to renew hope.

The first two verses of this piece are in themselves a complete poem by Robert Louis Stevenson and may be read in their own right, but Bell, who had decided to set this Stevenson poem to music remembered that he had heard a third verse somewhere which had particularly loved. Eventually, he tracked it down to a sermon by the great New Testament scholar, N.T. Wright, a sermon on John 20:1-18, on that dawn in the garden of Resurrection, preached when Wright was the bishop of Durham. Bell wrote to Wright thinking that perhaps he had access to some fuller version of the Stevenson poem not published in anthologies, but it turned out that Wright had, himself, composed this final verse to draw the beauty of Stevenson’s high-romanticism into the deeper and more rooted beauty of the Gospel. That verse by N.T. Wright is now the final verse of the lyric as it is printed here. Working with this material from the 19th and 21st centuries, Bell realised that the song required a ‘bridge’ or middle section and therefore wrote two further verses himself, which he inserted between Stevenson’s lyric and Wright’s coda. And from these three different strands of writing a new poem, a new ‘whole’, with its own form and beauty has emerged.

Preaching on Easter Day, in Durham Cathedral, Wright had opened his sermon by chanting the whole first verse of the Stevenson poem and then commented:

Impossibly romantic, you will think. How could the Bishop allow Easter morning to be subverted, trivialized even, by Robert Louis Stevenson’s high Victorian sentiment? Yes, all right, morning is indeed beautiful, and so for that matter is evening, as in the poem’s second stanza; but how can you go back to that old romantic vision? Hasn’t the whole twentieth century, not to mention what’s already gone of the twenty-first, made it impossible to return to that dreamy, pre-Raphaelite world? Don’t we have to be a lot tougher than that these days?

Wright goes on in his sermon to make the case for beauty both as part of the Gospel and something that is desperately needed in the modern world.

Among the many crises we face in our world is a crisis of beauty, and the fact that we can talk at length about everything else – money, the environment, sex, political corruption, not to mention Newcastle United – and only bring in beauty as an afterthought tells its own story. Perhaps it’s time to turn things around the other way, and start with the question of beauty and work in from there.

After a beautiful exposition of the Gospel itself, Wright asks:

But what has it got to do with beauty?

Everything. Perhaps surprisingly, the word ‘beauty’ occurs very seldom in the Bible. When it does, there are two main focal points; human beauty (often with a health warning; this doesn’t last!) and, particularly, the beauty of the Temple. If this is the place where the living God is to dwell, against the day when he will flood the whole of his beautiful creation with his presence, then the Temple must be made, and was made, as a supreme object of beauty.

Yes, it is true that beauty divorced from goodness and truth, cut-off from its origin in the beauty of God, may decay into a mere indulgent aestheticism, but the Resurrection of Jesus in that beautiful garden gives a chance to begin again, rooting beauty where it really belongs.

After all, if new creation has begun, if beauty has awoken afresh in the new Temple, the living home of the living God, as he awakens from the tomb, and if beauty is now let loose in all the world, it will rightly generate new forms, new possibilities, new delights. It will come closer and closer to its two senior cousins, Love and Truth, showing with them how to avoid the other false polarization, a brittle objectivity and a collapsing subjectivity, because it will be kept in place by the work of image-bearing, Spirit-filled human beings as they reflect the glory of God into the world and the glory of the world back to God.

It is at that moment in the sermon that Wright gives his own verse:

Let Beauty awake, in the morn from the cool of the grave,

Beauty awake from death;

Let Beauty awake,

For Jesus’ sake,

In the hour when the angels their silence break

And the garden is bright with His Breath.

The verse which Steve Bell remembered and wove into his song.

Bell’s own verses in ‘the bridge’ deepen the theme even further. We are not simply the detached beholders of God’s aesthetic, looking in on beauty’s garden from the outside. We too are called to be gardeners along with Christ to

Furrow the soil at our Saviour’s behest

And bury the seeds of our own life’s death

And suffer God’s glory to grow

There is a wonderful, double sense in Bell’s use of the word suffer here. At one level he is using it in the older sense, meaning to allow something to happen, but of course it must carry the modern sense of the word suffer too. Somehow, our own suffering offered to God might become not only a furrowing of the soil, but the sowing of the seed, every little act of letting go can be a sowing of ‘the seed of our own life’s death’, those who sow in tears will reap with songs of joy. But Bell does not use the word sow, he uses the word bury and surely that is to give some Gospel, some Good News, to those who mourn, those who feel in their grief that they have buried their life’s best hopes.

In the second of his stanzas, Bell moves us on from being gardeners, all of us, to being ‘the priests of all that is made’ who ‘gather the greatness of creation’s praise from the depths of the earth below’. Here there may be a gentle allusion to the work of two other poets. In his poem ‘Providence’ George Herbert says:

Man is the worlds high Priest : he doth present

The sacrifice for all ; while they below

Unto the service mutter an assent,

Such as springs use that fall, and winds that blow.

And in his poem God’s Grandeur, G.M. Hopkins speaks of how the grandeur and glory of God charged into the very being of the world, will ‘gather to a greatness’. Bell fuses these two sources and calls us, even in the midst of our grief, to be the priests who help to gather that greatness. What gives us the courage to do so, what wakens us to the greatness of our calling? It is the Good News that beauty itself has awoken in Christ ‘from the cool of the grave’ and ‘the garden is bright with his breath’ as ‘beauty awakes from death’.

For another exposition of this song lyric, see transcript of Jarem Sawatsky’s homily preached at the funeral of a mutual friend:

Living Beauty Awake…