The feast of the Holy Innocents falls grimly on the fourth day of Christmas. Of the four gospels, only the Gospel of Matthew (2:1-18) records this horrific story of King Herod, who, in a wicked attempt to protect his power base, ordered the massacre of innocent children in Bethlehem. This is a familiar story to our ears and seems entirely credible, for, indeed, Herods still thrive today.

According to Matthew, King Herod, himself a Jewish puppet king of imperial Rome, learns of the birth of one born King of the Jews from visiting magi (Persian wise men) whose ancient, astrological arts alerted them to a historical event of cosmic consequence, enough that they left behind everything they knew, all comforts and securities, to locate and pay homage to the infant Jesus.

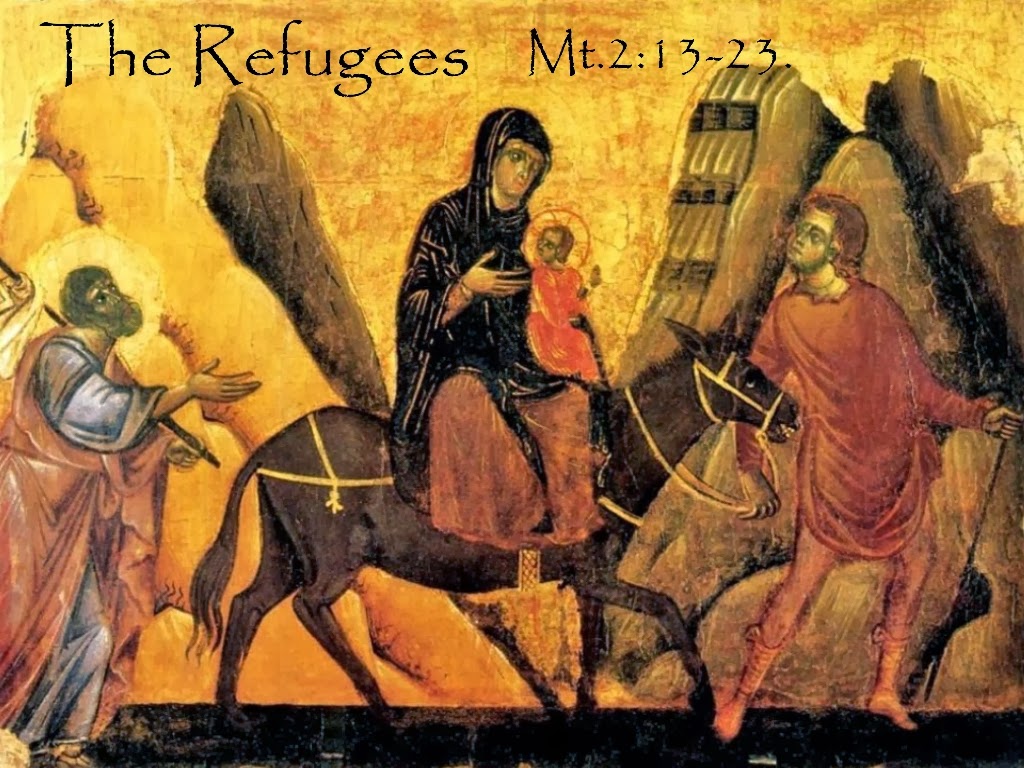

Herod was less inclined to embrace such an advent-ure. He would sooner slaughter innocents than loosen his grip on power, and he remorselessly did then what tyrants remorselessly do now. Indeed, the modern-day daughters and sons of Syria, Iraq, Palestine and Central America (among others) know him all too well. Herod’s monstrous cruelty set off a caravan of refugees which included the Holy Family, fleeing to Egypt for safety.

But must we tell this story now? It comes as a shock, especially at this time of year. It falls as a dark and heavy thud in the midst of our cosy-warm Christmas narrative that has been tamed and sentimentalized (fit for ‘family viewing’) to shore up a worldview perhaps more in keeping with Disney than the sometimes grim realism of the gospels. One is tempted to think that the ancient architects of the Church calendar year erred in judgment when they enshrined this remembrance so close to Christmas. Or, perhaps, we might consider that this impolite intrusion into our after-Christmas glow has been divinely inserted to force us to engage us with the sometimes grim reality of where we ourselves currently are.

For example, in my own Canadian context, it only falls to our recent history of Indian residential schools to remind our ‘glowing hearts’ how easily we would trade the lives of innocent children for a vision of prosperous well-being unhindered by inconvenient others. An estimated 6,000 First Nations children died in those schools prior to 1920, after which our government simply quit counting.

More currently, given the overwhelming evidence of climate change and the alarming predictions of unprecedented misery due to climactic shock, it is unsettling to think of a future generation of innocents dispossessed and dying as a result of our current claim to comforts and privileges over and against their right to life. This is a most insidious villainy, for who could be more defenceless than the not-yet-conceived? The menace of Herod, it appears, lies not only back in time or over the sea, but around and within as well.

And so, the gospels don’t let us off easily. Jesus—light from light, true God from true God—enters history as a vulnerable victim of Herodian cruelty, not aligned with the settled and powerful, but rather with the dispossessed and fleeing. Indeed, the One whom the Old Testament prophet-poets laud as our rock and refuge is now revealed as a refugee.

This shouldn’t surprise those of us who are familiar with the end of the story. For this divine refugee’s earthly life was ended (again by fiat of the powerful) on a cross hung between the despised and rejected, but with the ghostly whisper of “whatsoever you do unto the least of these, you do unto me” hanging uncomfortably in the air as well.

But what shouldn’t surprise us still does. For in our fallenness we perennially associate power, privilege and well-being with divine favour. It is only a small step to where we similarly associate weakness, poverty and suffering with divine disfavour, which allows us to blithely visit judgment and cruelties on those so disadvantaged. Our language is riddled with almost satanic parodies of the Gospel. “God helps those who help themselves” and “You can be anything you want to be if only you put your mind to it” come to mind. These words ring with a bitter cruelty in the ears of ones like my foster daughter, a woman of Oji-Cree descent, who bears on her soul the scars of five generations of institutionalized racism and forced displacement wrought on her people by European settler peoples of Canada.

Yes, we must tell this story now because it is integral to the meaning of Christmas.

But there is a double scandal here to consider. Not only does this feast interrupt our comfortable narratives, still strewn with wrapping paper and remnants of good things to eat, but linked as it is to the Easter story, by this revelation of God’s solidarity with the despised and rejected, is the equally astonishing revelation of God’s ready forgiveness of his victimizers. For on the cross, Jesus prays, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” These words must be heard alongside his equally challenging “whatsoever you do unto the least of these, you do unto me” if the Gospel is to be fully heard in all its bewildering and scandalous glory.

Christmas is a startling abruption long before it is a warming fireside. To miss this is to miss it all. God, it seems, is not OK with things as they are. And if we are to pray “thy kingdom come” with Christian integrity, we must envision a kingdom defined by solidarity, inclusion and forgiveness rather than a kingdom defined by self-interest and exclusion.

If you let your imagination warm to this, there is magnanimous, even cozy, warmth indeed.

________________________________________________________________

Below is a song called Refugee that I wrote with Malcolm Guite. The lyrics are taken from Malcolm’s sonnet of the same name. You can watch him recite the original sonnet at the bottom of this page.

REFUGEE

Music by Steve Bell

Lyrics by Malcolm Guite and Steve Bell

Appears on the 2012 CD release: Steve Bell / Keening for the Dawn

We think of him as safe beneath the steeple,

Or cosy in a crib beside the font,

But he is with a million displaced people

On the long road of weariness and want.

For, even as we sing our final carol

That hounded child is up and on the road,

Fleeing from the wrath of someone else’s quarrel,

Glancing behind, and shouldering their load.

And shouldering their load

While Herod rages still from his dark tower

Christ clings to Mary with fingers tightly curled.

The lambs are slaughtered by those men of power,

And death-squads spread their curse across the world.

How terrible, how just and how ironic

That every Herod dies and comes alone,

Defenceless as the naked embryonic

To stand before, the Lamb upon the throne.

The Lamb upon the throne.

I can’t resist the burning urge for turning

This song into a cautionary tale.

For the saviour whom this song has been discerning

Once occupied the belly of a whale

To reach as deep as love can ever fathom,

To rescue from the tentacles of hell,

The wretched, the beleaguered and forgotten,

Surprisingly, their enemies as well.

Their enemies as well.

Bonus: Watch Malcolm recite his original sonnet: Refugee